|

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

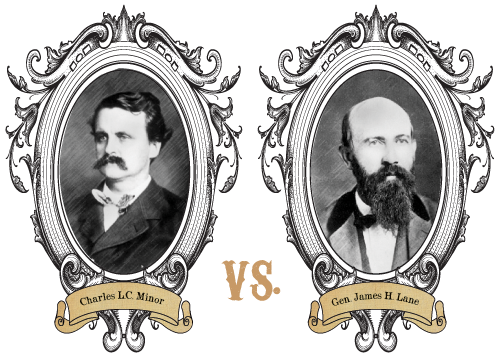

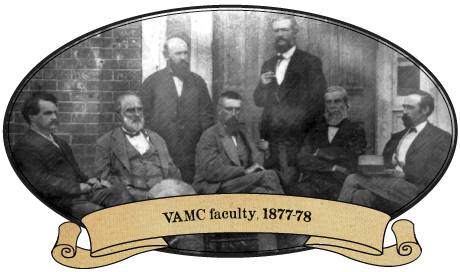

Charles L.C. Minor, the first president of Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (VAMC), was hired from Sewanee, where he had taught Latin and led the preparatory school. Earlier the president of Maryland Agricultural College, he held a master's degree from the University of Virginia and a doctor of laws and had served as a combat officer in the Confederate Army, reaching the rank of captain. "A fine-looking, robust man [with] a reputation of being an athlete and an excellent boxer," notes the late Col. Harry D. Temple (industrial engineering '34) in "The Bugle's Echo," Minor had come to VAMC highly recommended by professional colleagues.

Gen. James H. Lane, commandant of cadets, had graduated second in his class at Virginia Military Institute and earned a master's degree at the University of Virginia and both a doctorate and a doctor of laws. Nicknamed "Gamecock," he taught math and military tactics at his alma mater and then in Florida and North Carolina before entering the Civil War at its onset. Paroled in 1865 as a brigadier general, Lane had been wounded three times. Temple quotes a VAMC cadet describing the general as "a stern old disciplinarian [who] handled the cadets as if he were still fighting old Grant."

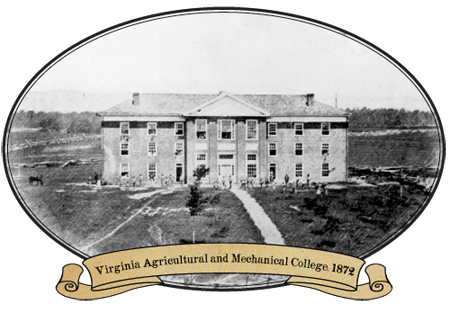

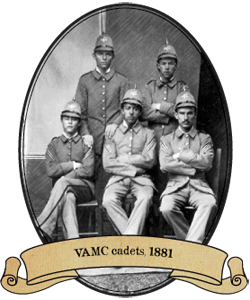

In early 1872, Virginia Gov. Gilbert C. Walker signed the bill allocating two-thirds of the state's grant monies to the Preston and Olin Institute in Blacksburg. The Methodist-affiliated "seminary of learning," which had fallen upon hard times, would be reorganized into VAMC—today's Virginia Tech. Preston and Olin's president, Thomas N. Conrad, who had fully expected to be appointed VAMC's founding president, dealt with the oversight by launching a bitter campaign against the new school's every move. As the editor of nearby Christiansburg's Montgomery Messenger, he hounded VAMC administrators and board members alike, accusing them of partisanship and sectionalism at best, ignorance and incompetence at worst. While other editors might have eschewed personal attacks for a more pragmatic assessment of the school's programs and progress, it became evident that the entire affair pitted a state-college/state-control construct against a state-college/local-control one. In other words, the school's growing pains were intense, if not historically significant. In his school history, "The First One Hundred Years," Professor Emeritus Duncan Lyle Kinnear notes that VAMC had opened its doors without "any clear-cut organizational plan of administration which could be used as a guide by either the faculty or the board." Naturally, such impetuousness invited chaos on the small campus. Faculty had a direct line to board members. Disputes arose over the school's curriculum. Political loyalties ruffled the faculty ranks. And at an 1878 faculty meeting, the president punched the commandant of cadets. Thus a matter of public record played out in newspapers statewide, VAMC's formative years hissed with dissension and discord better suited to Dickens or Dostoevsky.

Minor's efforts as president notwithstanding, the pro-military faction continued to hold a solid line. No consensus for properly disciplining the young men could be reached; and in an already contentious climate, confrontation was imminent.

Lane immediately requested a faculty meeting during which he presented a volatile speech that Minor was compelled to describe in his August 1878 president's report to the board of visitors: "Gen. Lane spoke at some length urging his view of the matter, exhibiting much excitement and heat, and using language discourteous to me. More than once he spoke of my seeking to set myself up as 'the great I am of the College.'" Apparently exhibiting considerable restraint, Minor "said nothing touching the question under debate, but proposed a postponement." Two days later, at Minor's request, the faculty again met to seek a resolution of the issue. Minor's report indicates that "Gen. Lane again spoke at considerable length with similar excitement and heart." Upon taking the floor for rebuttal, Minor was repeatedly interrupted by Lane, who refused to desist, despite being "ruled out of order" by the meeting's chair. "The character of his interruptions," Minor wrote about Lane, "may be judged from his words in answer to the presiding officer, very loudly and resentfully uttered: 'Order, the devil, this is a question of veracity.' He rose from his seat and advanced on me, and demanded with loud offensive and threatening tones and gestures, whether I meant to impeach his veracity." Minor coolly responded to Lane that "if he would have it so, it must be so." Then, Minor recounts, Lane "shook his fist in my face, grinding his teeth and crying aloud in rage and I struck him." It was the punch heard 'round the state—and the public was fit to be tied.

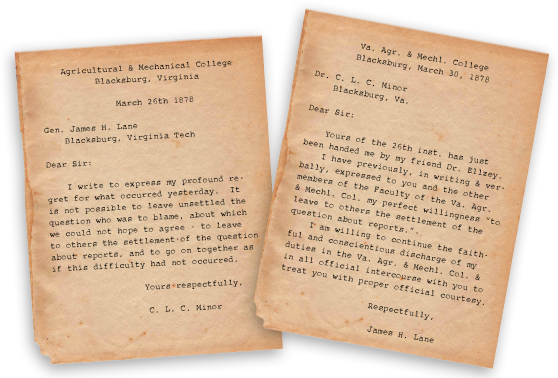

The board of visitors soon after announced a "dubious professional reconciliation" between the two men. If only on paper, Minor and Lane managed to play out a careful decorum, both expressing a willingness to put conflict behind them and proceed with the school's best interests. Later at a called meeting in August, the board received from Minor a full account of the fistfight, along with his most comprehensive assessment to date of the school's programs and operations. Lane, incidentally, was never required to defend his actions. Undeterred, much of the state continued to call for Minor's resignation. Bad press persisted, sometimes front-page, often erroneous. The school's growing pains had become intolerably painful.

Confident that Minor would find the military model objectionable, the board announced his removal from office before the year had ended. At the same time, political control of the state had shifted to a party hell-bent on dissipating the debt Virginia carried as a result of the war and the ensuing reconstruction. Called Readjusters, these politicians not only won control of the legislature, but also succeeded in electing a governor from their party. In keeping with the new face of state politics, a new board of visitors, Readjusters all, was appointed to serve VAMC. The new president, John Lee Buchanan, promptly reorganized the college, notes Kinnear in his 1972 publication, "especially the military department, along lines which have survived to the present time." Leaving Blacksburg, Minor settled in Winchester, Va., where he purchased Shenandoah Valley Academy, later teaching in Baltimore and at Episcopal High in Alexandria, Va. He died in 1903 in Albemarle County, Va. Lane, who would remain on as commandant of cadets through the next year, initiated changes in the military program to align it more closely with the program at Virginia Military Institute. In 1888, VAMC President Lunsford L. Lomax, a West Point graduate who had served the Confederacy as a major general, used a legislative appropriation to erect Barracks No. 1, now known as Lane Hall in a nod to the first commandant. The centerpiece of the Upper Quad, Lane Hall remains one of the oldest buildings on campus. Lane, who moved on to teach in Missouri and at Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama, died in 1907.

Long healed from the black eye dispensed by its fighting founding fathers, the university remains committed to its land-grant mission of service and sharing knowledge. Revealing an institutional mettle likely ingrained at its core, the little school in the wild Southwest took on change and flourished. One might even say Virginia Tech—and the Hokie Nation—earned the right to lean upon the trait that's among its most valuable: that fighting spirit—minus the fists.

The images are courtesy of the Historical Photograph Collection, Digital Library Archives, University Libraries, Virginia Tech; and were used in "The Bugle's Echo: A Chronology of Cadet Life at the Military College in Blacksburg, Virginia," by Col. Harry D. Temple. The text of the Minor and Lane letters appeared in "Report of the President to the Board of Visitors, August 1878," Special Collections, University Libraries, Virginia Tech. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||