| NASA's extraterrestrial samples are in good (Hokie) hands

If you've ever wondered what happens to moon rocks and other extraterrestrial specimens collected by NASA, you'll be glad to know that they're well taken care of by a Virginia Tech alumna.

If you've ever wondered what happens to moon rocks and other extraterrestrial specimens collected by NASA, you'll be glad to know that they're well taken care of by a Virginia Tech alumna.

Lisa Vidonic (industrial and systems engineering '00) spends her days ensuring that lunar rocks, Antarctic meteorites, and cosmic dust are perfectly preserved and safely distributed to scientists throughout the world for research. Vidonic works for Lockheed Martin Space Operations as the facility engineer for NASA's Astromaterials Research & Exploration Science Division at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"The scientific value of the collection could be jeopardized if the materials aren't preserved and maintained," notes Vidonic, who helps oversee the space center's Lunar Sample Facility as well as the Meteorite Processing, Cosmic Dust, Genesis, and Advanced Curation laboratories. "The cabinets housing the samples are purged with clean, dry nitrogen gas and kept under positive pressure to keep contaminants out," she says. "My job is to oversee the processes that keep the labs clean--filtered air, ultrapure water, clean nitrogen."

Cosmic dust, Vidonic explains, is collected by planes sent into the upper atmosphere; sample particles from the dust are separated in the lab. The Genesis Lab will house solar wind, which is composed of elements from the sun and is currently being collected by spacecraft.

Vidonic's work with these samples is good training for her next job. In the Advanced Curation Lab, Vidonic and other engineers and scientists on NASA's Mars Return Sample Handling Team are developing a prototype glovebox with a robotic arm to prepare for samples that someday will be brought back from Mars.

NASA's Mars Program has recently surveyed much of the planet with the space probe Odyssey, but it will be several years before a future landing vehicle brings back samples. "When samples do come back from Mars," Vidonic says, "we have to be prepared to protect the Earth from them as well as protect the samples from Earth contamination."

Preservation through conservation

The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, which was created to ensure the future of elk and other wildlife, as well as their habitat, has conserved and enhanced more than 3.3 million acres of land--an area 50 percent larger than Yellowstone National Park. The foundation hopes that its current "Pass It On" campaign will allow the group to add two million more acres to that total by 2005.

The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, which was created to ensure the future of elk and other wildlife, as well as their habitat, has conserved and enhanced more than 3.3 million acres of land--an area 50 percent larger than Yellowstone National Park. The foundation hopes that its current "Pass It On" campaign will allow the group to add two million more acres to that total by 2005.

With 23 years of experience in the forest products industry, Rich Lane (forestry '81), the new president and CEO of the organization, promises to be integral to helping the organization accomplish its goals.

His agenda includes raising awareness. "Our biggest problem is that many people do not understand the urgency of land conservation," says Lane. "We are losing wildlife habitat at an alarming rate. I view this not as apathy, but rather a lack of knowledge."

While Lane appreciates efforts toward conservation, and thinks the nation's conservation ethic is growing, he says he "was very involved with, and frustrated by, the public timber wars affecting the West. The extreme environmental groups only seek to lock things up. True conservationists realize that we must protect and use our lands and associated resources carefully, so that they can sustain us forever. Unfortunately, many of our public school systems do not teach this conservation ethic."

Lane hopes to pass on his own passion for conservation from a childhood spent in the great outdoors. "There is something patriotic about continuing a way of life somewhat similar to what our country was founded on. Freedom to move about, live a little on the wild side, hike in the dark, take risks, howl at the moon."

Creating community in Blacksburg

While hiking the Appalachian Trail one summer after quitting his job as a computer programmer in Washington, D.C., John Imbur (history '91) stopped in Blacksburg to visit old friends. That's when he heard of plans for Shadowlake Village, a Blacksburg co-housing community, and decided to return to join the project upon completion of his hike. "I fell in love with the land, the people involved with the project, and the shared vision of what was being created," says Imbur, explaining his reasoning in returning to participate. "I get to own my house and live in an intentional community."

While hiking the Appalachian Trail one summer after quitting his job as a computer programmer in Washington, D.C., John Imbur (history '91) stopped in Blacksburg to visit old friends. That's when he heard of plans for Shadowlake Village, a Blacksburg co-housing community, and decided to return to join the project upon completion of his hike. "I fell in love with the land, the people involved with the project, and the shared vision of what was being created," says Imbur, explaining his reasoning in returning to participate. "I get to own my house and live in an intentional community."

Co-housing is a model of development that serves as an alternative to many of the problems America faces with increasing urban sprawl, pollution, and what community members call the "increasing isolation in cookie cutter neighborhoods." Members of Shadowlake--the majority of whom are Virginia Tech alumni, faculty, and staff--are intentionally forming an intergenerational, eco-friendly community.

Features that the residents are especially proud of include the "pedways" meant only for pedestrians (cars are kept to the periphery of the neighborhood), the common house (with a playroom, a library, and a laundry), and the common gardening area. The property is near enough to downtown Blacksburg to allow many of the dwellers to bike or walk to work. And although all units have porches to facilitate community, the site was designed to allow for privacy as well.

Nathan Kranowski (M.S. accounting '77), known as the grandfather of the group, encapsulates the general zeitgeist of the community: "The reason to join is not because you want to buy a house. The reason is because you want to live a certain way."

You can learn more about Shadowlake Village at http://www.shadowlakevillage.org.

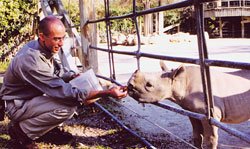

Feeding time at the zoo

What do black rhinos, flamingos, vampire bats, and invertebrates have in common? They have all been or are currently under the watchful eye of Mike Maslanka (wildlife science '93), the nutritional services manager and staff nutritionist at the Fort Worth Zoo in Fort Worth, Texas. The zoo's nutritional services department cares for all the animals in the zoo's collection, and "cares for" is the right phrase! "The zoo is so particular about the produce it accepts that the food is better than what most of us buy at the store," says Maslanka.

What do black rhinos, flamingos, vampire bats, and invertebrates have in common? They have all been or are currently under the watchful eye of Mike Maslanka (wildlife science '93), the nutritional services manager and staff nutritionist at the Fort Worth Zoo in Fort Worth, Texas. The zoo's nutritional services department cares for all the animals in the zoo's collection, and "cares for" is the right phrase! "The zoo is so particular about the produce it accepts that the food is better than what most of us buy at the store," says Maslanka.

Maslanka's job has sent him to such faraway places as Alberta, Canada; the Yucatan Peninsula; and many locations in China. Although he's worked with myriad species during his travels and in his current position, he hasn't yet visited what he terms the "mecca of the zoo world": Africa. Maslanka says that it's "almost surreal the number of amazing species to observe there."

Maslanka's jet-setting life hasn't made him forget his roots, though. "Every fall I get the chance to return to Tech to lecture for a few animal science classes. I make the trips as much to teach [students] about wildlife nutrition and physiology as to instill the importance of 'thinking outside the box,'" said Maslanka. He's interested in encouraging students as well as fellow Tech grads. "If other alumni get the chance to see what I do, then they may feel all the better about Tech regardless of where we are or what we have ended up doing. If the background and education I received was enough to allow me to travel and do what I really love, theirs can lead them anywhere they are inclined to let it."

|