|

Memoirs of Homer Hickam '64 are grist for by Su Clauson-Wicker |

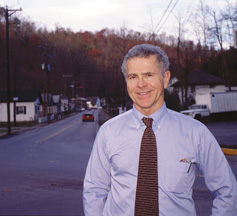

Woe to anyone who drove up wanting a fast fill-up and a pack of nabs on the day Homer "Sonny" Hickam Jr. (industrial engineering '64) returned to Coalwood, W.Va.

That afternoon last November, Lynn Hamilton's Country Corner was more jammed with humanity than a quick-service store in a coal-country ghost town had any right to be. The overflow milled around the gas pumps in their Sunday suits and hunting outfits, almost spilling onto Route 16. Inside, the Methodist women were cutting cake and serving punch.

The crowd outnumbered the Coalwood Methodist and Pentecostal congregations combined as folks from all over McDowell County turned out to get Hickam's autograph on their copies of Rocket Boys.

October Sky, the movie based on Hickam's adolescent adventures building rockets in the coalfields, wouldn't be out until February, but these loyal folks had his memoir on back order in every bookstore within a 50-mile radius.

"Rocket Boys is the first book I've read in 20 years," admitted one burly, retired miner. "I read it to remember how things used to be. Sonny, you did a good job of telling it like it was."

Hickam, who brought along Linda Terry, his new bride, was dapper in a gray suit, somehow still crisp after the seven-hour drive from their Huntsville, Ala. home. No matter that he is 56 years old, an acclaimed author, and a retired NASA engineer who trained astronauts, he's still "Sonny" to these folks--a name he outgrew in Vietnam--either that or "Homer's boy," the son of the mine superintendent--not the football-player son, but the one who launched rockets. And despite the fictitious names in the book, the people gathered here see themselves and their neighbors in his memoir.

"I know I'm Leon Ferro; I'm the guy who built the rocket nozzles," said Bill Bolt, former mine machine-shop foreman. "That man over there is O'Dell's dad, and those guys played softball with Sherman." (O'Dell and Sherman were original rocket boys; they are one composite character in the movie.)

"I don't know anything about the girls; I was a married man," Bolt added.

Rocket Boys is a simple story of six boys in Coalwood who witnessed the Soviet satellite Sputnik streaking across the night sky and decided to build their own rockets, despite numerous difficulties. Hickam set the course for this story about rockets, family tension, young love, and the shifting fortunes of a once thriving coal town in the first line of his book:

"Until I began to build and launch rockets, I didn't know my hometown was at war with itself over its children, and that my parents were locked in a kind of bloodless combat over how my brother and I would live our lives. I didn't know that if a girl broke your heart, another girl, virtuous at least in spirit, could mend it on the same night. And I didn't know that the enthalpy decrease in a converging passage could be transformed into jet kinetic energy if a divergent passage was added. The other boys discovered their own truths when we built our rockets, but those were mine."

Hickam is remarkably humble about the success of his second book. (Torpedo Junction, his historical account of German U-boat battles off the U.S. Atlantic coast, was published by the Naval Institute in 1989.)

"I never intended to write about myself," he says. "Having my work made into a movie was never one of my goals. How I came to write Rocket Boys is a miracle. It has amazed me as much as anyone."

It began in December 1994, when the editor of Smithsonian Air & Space called Hickam with an urgent request for an article to fill a space in the next issue. Hickam had the reputation of being fast. He glanced at the small rocket nozzle he was using as a paperweight, and as he talked to her an idea began to form.

"You know, when I was growing up, some boys and I--we were miner's kids--built rockets. We won a medal at the National Science Fair."

"Well, fax it to me and we'll see," the editor said with a noticeable lack of enthusiasm.

Hickam wrote the article in three hours. "Memories were tumbling out of places I had not looked for decades," he says. "The next day Pat, the editor, called. Would I send pictures? The magazine was going with the story as a major feature."

He was astonished at the reaction when the article came out. Letters poured in from all over the country. "People wrote that the story gave them hope, because if we, the children of coal miners, could not only aspire to such heights, but achieve them, then anything was possible," he says.

Some even wanted him to speak to their children. But best of all, a small motion picture production company wanted to know if he'd sold the rights to his story.

"I thought, 'Well, maybe a large production company might be just as interested.'" he says. "I decided to tell the fuller story and began writing a book about those long-ago days in Coalwood. Within a year, I had a contract with Universal Studios for a major motion picture to be based on a book I was still writing. When I finished the manuscript, I enjoyed watching a spirited auction for it by top New York publishers."

Rocket Boys was published by Delacorte Press in the fall, with an audio version released by Simon & Schuster. It has been nominated for a National Book Critic's Circle Award and was selected as a New York Times Notable Book for 1998. Hickam took off in September on a book-signing tour that zigzagged across the Southeast and over to London.

"What is it like, having your wildest dreams come true?" asked the daughter of one of his former Coalwood neighbors.

"Linda and I still have to pinch ourselves and ask if this is really happening," Hickam answered. "I wish I could say it's all been wonderful, but it hasn't. Sometimes it's extremely stressful--especially having a movie made of your life, being interpreted by others who never lived in West Virginia, never walked your shoes."

|

Although many authors are unwelcome on the movie set, Hickam was paid handsomely by Universal to be a technical consultant during the filming of October Sky in Tennessee last spring. "Some things they were trying to do just wouldn't happen in West Virginia," he says. The rather innocent West Virginia 14-year-olds were first portrayed as having the savvy of an urban gang. Hickam got that changed, as he did the scene where his father let out a string of curses in argument with his mother. "Dad didn't do that," Hickam says.

Hickam was able to help when Jake Gyllenhaal, the film star who portrayed him, wanted advice about the accent. "I was worried the movie might have us talking in a hillbilly drawl from Coal Miner's Daughter," Hickam says. "We grew up with cable television. Our accent was more Midwestern than anything else." At his recommendation, Universal hired speech professor Emily Sue Buckberry, Hickam's childhood friend, to help Gyllenhaal, and other actors including Chris Cooper and Laura Dern, to develop the appropriate speech patterns. |

Hickam had other expertise that was in demand on the set, some of it honed at Virginia Tech. At one point, director Joe Johnston stopped cameras so that Hickam could show the young actors how to use a slide rule.

|

"That thing was older than any slide rule I used at Tech," Hickam says. "Of course nobody on the set had any idea how to use it, so I demonstrated how to multiply 2 x 2, and that is what they did in the scene where they were calculating rocket velocity."

Slogging through the mud on the movie set quickly lost its glamour after a few days, but Hickam became fascinated with the mechanics of making a movie. The high point was hanging out with the special effects guys sending off rockets. |

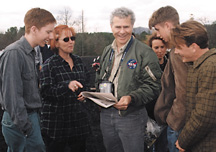

| Homer Hickam '64 (center) jokes with the actors who play his boyhood friends during a break from filming October Sky. |

"All their rockets were free-flying, and they used commercial rocket engines--I was glad of that," Hickam says. "But they weren't as fast as the ones we sent up 40 years ago--the camera wouldn't have been able to catch ours."

| During the shooting, Hickam and his wife became good friends with director Joe Johnston (whose credits include Jumanji and The Rocketeer) and stayed at his home in Beverly Hills. "Movie people are artists; they have feelings just like everyone else," Hickam says. "I learned that they don't care if you say 'So-and-so wouldn't do that.' They care if you tell them people will laugh at them if so-and-so does that in the movie."

"Homer, selling a book to Hollywood is like selling your baby to the slave traders," Johnston warned Hickam early in the process. |

|

| October Sky's main characters pose during the filming of the movie last spring. From left to right, they are: Chris Owen, Will Lee Scott, Jake Gyllanhaal (who plays Homer), and Chad Lindberg. |

Hickam says, however, that he sold Rocket Boys to some very classy slave traders, that he got his licks in during script development sessions, and that he is very satisfied with the results. "They took my baby and dressed her up in finery, although there are parts of her I don't recognize," he says.

Hickam shows no signs of losing momentum. In between book tours, he's been spending 12- to 15-hour days at the computer, working on a techno-thriller tentatively titled Back to the Moon. "It's about the next time the United States goes to the Moon with a human crew, and it's supposed to come out this summer for the 30th anniversary of Apollo 11," he says. "The crew has to use the space craft inventory they have today, meaning the Space Shuttle, which was built for low-earth orbit. It's solidly based on fact; I once wrote a memo about how we could use the hardware and software we have available to go to the Moon. NASA circulated if for awhile and let it go."

He's also considering a sequel to Rocket Boys, but fellow Hokies won't be seeing any Blacksburg landscapes. It's a Christmas story set in Coalwood.

"I've always intended to be a writer--to freelance, to have a second career in retirement," he says, "ever since grade school, when my teacher used to mimeograph my stories and pass them out around school. My writing got me through VPI. I made respectable grades in English; that wasn't always the case in my other classes."

After graduating from Tech in 1964, Hickam went into the U.S. Army's officer training program and served in Vietnam. "I thought it was going to be the great adventure and that I was indestructible," he says. "Then I saw combat and grew up a lot." He was awarded a Bronze Star for leading a counterattack against the North Vietnamese in the little town of Ban Me Thuot.

Vietnam was the inspiration for his first major work, "a long, boring novel I've still got in a trunk," he says. But soon afterward, while stationed as an administrator for the reserves in Puerto Rico, Hickam took up scuba diving and began writing about the topic for magazines. While he worked in army missile operations, he added space writing to his repertoire.

In 1981, he grasped the dream of his youth when he became a NASA engineer at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. Over the next 17 years, he trained astronauts, talked them through their science experiments while they were in orbit, and met with the Russians who launched Sputnik I. In November 1997, a few months before he retired, an astronaut friend carried a piece of Hickam's old Auk rocket nozzle into orbit aboard the space shuttle Columbia.

At Virginia Tech, however, Hickam may always be best remembered for another high-powered endeavor: the first Skipper cannon, which he helped to build and fired in 1963.

"I spent a lot more time building that cannon than I ever did studying at Tech," he remembers. "Butch Harper (business '64) and I were the ringleaders. We made the mold in the industrial engineering department, and my dad donated discarded brass gears from the Coalwood coal mine to cast it. Legend has it that cadets donated brass belt buckles and buttons for it but actually they fell far short of the pounds that were needed."

Hickam mixed a concoction of black powder and gun powder, stuffed it in plastic mustard bottles, and pitched them down the tube. When he and George Fox (mechanical engineering '64) tested the charge on the golf course, it didn't sound very loud, so Hickam changed the combination and quadrupled the charge for the Thanksgiving Day football game at Roanoke's Victory Stadium.

When Skipper went off, it knocked down some of the football players, including his brother Jim (history '63), and sent a shock wave through the opposing crowd.

"You could literally see the shock wave," Hickam says. "I was told it also cracked some of the glass in the press box. I diminished the charge accordingly after that."

Home | News | Features | Research | Philanthropy | Alumni | Classnotes | Editor's Page