| Home

Contents

Sports

Alumni

Classnotes

Editor's Page

Philanthropy |

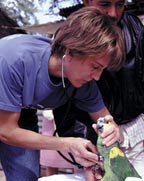

From the field: Trials and triumphs of an international wildlife vet

by Kimberly Richards-Thomas '93, M.A. '95

When Sharon Lynn Deem (biology '85;

DVM '88) and her fellow researchers set up camp on the vast steppes of eastern Mongolia, it

seemed they had found the perfect spot to conduct

their study. The purpose of their project,

sponsored by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS),

was to provide local officials with health

For the first few days, everything went smoothly. They

located several herds and successfully examined about 50

calves. But trouble began on the fourth night, when lightning

struck the plains. For the first few days, everything went smoothly. They

located several herds and successfully examined about 50

calves. But trouble began on the fourth night, when lightning

struck the plains.

At first they had nothing to contend with but a small

brush fire, and they tried to douse the flames. But after three hours

of racing to contain the fire as it rapidly spread, they knew

they were in danger.

"For the next few days, it was like in the old

Westernswe moved around to the back side of the fire when it was

moving one way. Then we burnt a circle around us as a fire break.

We had this little oasis of green, and around us were hundreds

of kilometers of charred grasslands," says Deem. When they

walked over the scorched landscape a few days later, she recalls, it

was littered with the burnt remains of mice, gazelle, and other

small animals.

Despite this and other major setbacks, the WCS team

collected enough information to assess the health-related

impacts of interactions between the gazelle population and local

herds of sheep and goats.

As one of three veterinarians with the WCS

Field Veterinary Program, Deem doesn't always face

such dire conditions in the field, but she does

encounter her share of hardships. Since joining the

program in 1998, she has persevered through political unrest, language barriers, bumpy

plane rides, and living in a tent for weeks at a time. She has stumbled upon an

anaconda, been charged by a silver-backed gorilla, hunted through "impenetrable

thorn-bush and an abundance of ticks" to track down a tapir in Bolivia, and

hiked more than 300 kilometers through record-breaking rainfall to

immobilize an elephant in the Congo.

Yet none of this overshadows

the rewards. Her field reports read like excerpts from

National Geographic Magazine. She travels

throughout Asia, Africa, and Central and South America, seeing places most

people only dream of visiting. She works regularly with a whole range of

rare, exotic, and endangered species, from blue-fronted Amazon parrots to

green sea turtles. And she contributes directly to conservation and health

initiatives on an international scale.

"It can be difficult," Deem says, "but

it can be beautiful." And she's not talking about

pretty sunsets. To her, beauty means coming

face-to-face with an animal in the wild, on its own termsa

troop of gorillas in an African rain forest or the maned

wolf she spent days tracking in Bolivia. "There are

times when I've been waiting for days in a blind for

one little animal, and I wonder why I got so much

education to sit there being bitten by mosquitoes,

and it's awful!" she laughs. "But then, when she

finally shows up, and here is this animal in front of

youit's just so different than working in a zoo.

Because it's their world, and you're just there trying to

learn about it to keep it intact."

Working to preserve areas of the natural world despite

rapid international development, the Field Veterinary Program

seeks that precarious balance between the needs of humans and

animals. Areas where human, wildlife, and domesticated

animal populations overlap, such as the edges of national parks,

demand particular attention because the diseases that pass

among these three populations threaten both people and animals.

This is where Deem does much of her work. Working to preserve areas of the natural world despite

rapid international development, the Field Veterinary Program

seeks that precarious balance between the needs of humans and

animals. Areas where human, wildlife, and domesticated

animal populations overlap, such as the edges of national parks,

demand particular attention because the diseases that pass

among these three populations threaten both people and animals.

This is where Deem does much of her work.

In the Gran Chaco region of Bolivia, for example, Deem

has worked extensively with the Gurañi Indians who live and

hunt on the outskirts of the Kaa-Iya National Park. Her

contributions to the region include long-term health evaluations of tapir,

armadillo, brocket deer, and several other species; analysis of

the effects of wildlife/cattle interaction in the area; and medical

training for the scientists and local veterinarians working on

this project.

She has helped educate the Gurañi Indians about

incorporating sustainable use, a concept that is sometimes the most

practical approach to global conservation. "The Gurañi Indians

have hunted and lived off these animals for hundreds and

hundreds of years. We're not saying, 'You've got to stop hunting, we

want to preserve everything.' We want to preserve species, even if

that requires some animals being killed at a level that ensures

the survival of the local people."

Because the Gurañi have been shown that their survival

depends upon change, they have willingly adapted sustainable

use practices despite centuries of tradition. They have learned

how to care for their domestic parrots in order to protect the

free-ranging parrot population, for example, and how to

monitor brocket deer health to maintain adequate numbers for

hunting. "When we point out that it's a different world than it was a

few hundred years ago, and we need to work in the context of

what it is now, people are receptive to that," the Tech alumna says.

Deem's interest in conservation began during her days

in Tech's Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary

Medicine. As a vet student, she spent two summers working on

projects in Africa, the first in Kenya, where she took a

wildlife management course, and the second in Zimbabwe. Deem

received funding for the Zimbabwe project from the U.S. Agency for

International Development to conduct both a gender-related

study on women's role with livestock and a veterinary study on a

disease called heartwater. Several years later, she returned to

Zimbabwe to study the epidemiology of heartwater while

earning her Ph.D. through the University of Florida.

Her focus on worldwide conservation made her a natural

fit for the WCS. Although there were no openings in the Field

Veterinary Program when she finished her zoo and wildlife

residency at the University of Florida, she joined WCS as a

clinician. Based at the Bronx Zoo/Wildlife Conservation Park,

WCS also runs the New York Aquarium and three other wildlife

centers located around the city. As a WCS clinician, Deem

contributed to the care of about 10,000 animals, including nearly

1,500 species of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

Today, when she's not traveling, she still conducts her research

from WCS headquarters at the Bronx Zoo, also the location of

the Wildlife Health Center, a premier medical and research facility.

At the heart of Deem's accomplishments is just

thatheart. Her love of animals comes through in her voice when she

talks about her work. Leaving her own cats in the care of friends

while she travels concerns her more than any hardship in the

field. And she says she cried the first three times she watched an

educational video WCS developed as part of the Bronx Zoo's

new Congo Gorilla Forest. After a graphic depiction of the

violent effects of deforestation and bushmeat trading in the Congo,

the video screen rises to reveal the park's gorilla population

enjoying their new rain forest environment behind a

floor-to-ceiling wall of glass.

Deem assumes she will eventually settle down to a

quieter lifestyle, but presently world travel suits her just fine. "I

really believe in what I'm doing right now. Will I be traveling like

this in five years? Who knows? But I want to stay involved in

conservation."

|