players he's seen--Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson.

players he's seen--Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson.by Su Clauson-Wicker

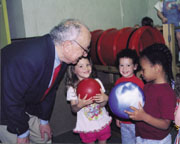

Seventy years have passed since Alfred "Alf" Knobler (ceramic engineering '38) graduated from PS 42 in the Bronx, but now he's back at his old elementary school and he's got things to tell the kids.

The book he'd been reading aloud on Jackie Robinson is set aside as Knobler recounts what it was like to picket Yankee Stadium when he was 15 years old. "We demanded that black players be allowed in the major leagues," he says proudly, remembering the incident. At 83, lively as an elf, Knobler rolls off to the fifth-graders names of legendary black  players he's seen--Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson.

players he's seen--Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, Jackie Robinson.

"These kids are so alive and wonderful," he says of the PS 42 pupils. "They love learning. Give them any chance at all, and they'll make it."

When Knobler lived in what was then an Italian, Irish, and Jewish immigrant neighborhood, he knew women up and down the street he affectionately called "Grandma." Now the 600 black and Hispanic youngsters at PS 42 shout, "Hi, Grandpa Alfred" when Knobler makes his weekly visit.

Knobler adopted PS 42 over a year ago after learning that students in this poor neighborhood consistently score above grade level in reading. He visited the school, found it little changed from the 1920s, and asked how he could help. Since then he's donated a baby grand piano and some used Broadway sound equipment, delighting students when he had Broadway sound technicians come to install it. But more importantly, Knobler gives his time as a regular volunteer, reading and discussing social history and politics with the children on a weekly basis.

Knobler is not trying to fill up idle time--he's still very involved as CEO of Pilgrim Glass in Ceredo, W.Va., stays active in numerous political and social causes, maintains a dizzying social schedule, and runs an import business serving 16,000 dealers in the glass and gift industry. Twice a year, he visits Virginia Tech, where he is a member of the College of Engineering's advisory Committee of 100, the Materials Science Engineering advisory council, and Ut Prosim Society.

Education, especially education for those perceived as disadvantaged, is extremely important to Knobler.

"Who made this country?" he asks, and you feel he's asked and answered his rhetorical question over many tables and many years. "The poor people made it--people who came here for a better life. Look at Virginia Tech. It was the same way. When I came to Tech, it was mostly poor kids trying to make it--bright kids who were first generation college."

Knobler fit this mold. He came to Tech from New York City in 1934, the baby of his family and the first to attend college. It was during the Depression, and the Jewish youth from the Bronx saw the southern university as a real deal at $120 a semester.

PS 42 is only one outlet for Knobler's passion for education. In 1982, on one of his trips to his West Virginia glass plant, he visited a Huntington childcare center started with Appalachian Regional Commission funds. The start-up funds had been exhausted, and the Children's Place was struggling for survival.

Knobler's solution was a chicken luncheon.

"I wrote letters to 26 CEOs in Huntington. They all came down to tour the place and look at the children through the polarized glass windows. Then we had lunch, and I made my pitch. I told them how important the Children's Place is in the county, the state, and even the country. 'Who's going to put up the first $100,000?' I asked."

Although Knobler didn't raise $100,000 from Ashland Oil, Inco Alloys International, and other Huntington based industries, he did raise $29,000--a godsend for the 100-child facility. He continues to raise money for the center.

"Mr. Knobler has been on our board for almost 16 years," says Children's Place director Marsha Dawson. "Everybody on the staff knows his name. He contributes beautiful Pilgrim glass prizes for our carnivals and staff events."

The Children's Place is a comprehensive child development center providing kindergarten, nursery school, and infant care. Its innovative special needs programs and superior care made the facility a winner of West Virginia's Exemplary Program award last year. At least one in five families served are subsidized by state Department of Health and Human Services; many others pay a reduced fee, based on their economic status.

Knobler has been a presence in the Huntington area (although he never moved from New York) since he founded Pilgrim Glass in 1949. The first thing he did was start a medical plan for his seven employees. As the plant grew in size and success, he added more benefits and became one of the few West Virginia employers actually happy to see a union voted in.

"I support unions; workers need someone to look out for their needs," Knobler says. "My concern has always been for the poor people. There is a crisis in what American working people are being paid. For most of the decade, their true earnings have been flat, while some top executives receive $10-million Christmas bonuses. America needs a raise."

"Pilgrim's wages are in the top bracket in the tri-state [Ohio, West Virginia, Kentucky] area," says Pilgrim plant manager Arnold Russell. "Is Mr. Knobler good to work for? Well, my 41 years here should give you the answer to that."

Wages are only one of the reasons why many of the 90 employees make Pilgrim their career employer, Russell says. They also appreciate the consistency of Knobler's leadership and thrill of working with hand-made glass. "Every day there is a challenge to make a new product or to make a product better; every day it's different," he says.

The company creates a variety of vases and other art-glass pieces, including cameo glass--the epitome of challenging glass work. Pilgrim is now the world's only producer of the multi-layered, multi-colored glass, made by casing one layer of molten glass upon another. The layers of glass, each with a different chemical composition, must have the same rate of expansion or the glass will shatter. In fact, 95 percent of Pilgrim's earliest attempts ended up in the garbage pile. "The breakage rate in those years would have disheartened any but the totally, foolishly dedicated," Knobler says. Now, after years of development, breakage stands at 5 percent.

Pilgrim has been generous with its glass. Knobler donates imperceptibly flawed seconds to the Virginia Tech YMCA Thrift Shop and several other charities. He also gives glass to the Children's Place for fund raisers and has donated sales from a recent Blacksburg exhibit to Virginia Tech's material science and engineering department.

When Knobler visits campus, he likes to reminisce to engineering and English classes about the old VPI. (His minority scholarships in English make him the department's only direct benefactor; he was stimulated by his humanities classes and knew their support was leaner than that of engineering departments. He also supports minority scholarships in materials engineering.)

"I knew the people these buildings were named for," he says. Materials Engineering professor Dan Pletta and YMCA Secretary Paul Derring were his favorites. They could talk for hours about social causes, as well as academics. In Derring especially, Knobler found a kindred spirit with a concern for justice and social action.

"Good people," he says, nodding in the direction of the old YMCA building where he spent countless hours in fervent discussion with Derring. "The good people never really die. You remember them forever."

Home | News | Features | Research | Philanthropy | President's Message | Athletics | Alumni | Classnotes | Editor's Page